Episode 16: Vincent Van Gogh’s Postman Joseph Roulin (1888)

[00:48]

VOICE 1: The uh, the postman. Uh, is a very distinguished looking fellow here. He’s very uh, regal, even though he’s just a postman, which, I don’t what to bring him down at all. But is in a beautiful uniform, double breasted. His beard is fantastic.

VOICE 2: His suit looks formal but his pose looks completely calm, relaxed.

VOICE 3: He seems uh, very personable. Like somebody you would, you’ve definitely seen or met or like asked for directions or something like that.

VOICE 4: And I… being a bearded gentleman myself, I think he’s just uh, a fantastic guy here in this painting. It‘s incredible.

VOICE 5: He’s probably very kind.

TAMAR: What makes you feel like he’s kind?

VOICE 5: His eyes.

VOICE 6: Sitting down for a serious talk. [laughs]

VOICE 7: Yeah.

VOICE 8: So he’s probably, like like, starting to have a conversation with you and he’s like understanding you, and like with a serious look on his face.

[01:54]

VOICE 9: He looks like he’s really listening to you and not just staring off into space. Unlike other portraits.

VOICE 8: Yeah, it actually like looks like he’s looking at you and listening to you.

[02:09]

Intro credits.

[02:45]

So I googled Van Gogh the other day, like you do. Well, like I do. I was at “van g,” four letters and a space, when google helpfully autofilled my options: van gogh museum, van gogh paintings, van gogh ear. Ugh. That damn ear. That fetishized little chunk of lobe, that finishing touch on Van Gogh Halloween costumes, why are we so obsessed with it? Why is it as iconic as his paintings? Why is there an actual 3-D-printed replica on display in Germany? I mean, I guess I get it: it’s a symbol of his crazy, of every artist’s crazy, of that kooky artistic temperament that separates a tragic genius from you and me. We’re shocked and repulsed and even kind of charmed by it. But that ear is also, I’m sorry to say, a symbol of everything that rankles art historians about the public consumption of art history. Because it’s a shortcut to generalization, to being satisfied with an icon, instead of getting uncomfortably close to the complexities of a painter and his work. And it leaves Van Gogh with little more than the reputation of the tragic and insane starving artist poster boy who only sold a single painting in his lifetime.

[04:21]

Examples of ear-obsessed Van Gogh slingers

Most people don’t know the gory details—and, to be fair, the exact circumstances are unknown—about how Van Gogh, the aimless and temperamental minster’s son, decided to become an artist in 1880 in his late twenties, and then moved to Paris in 1886, and two years later rented a house in the southern French town of Arles to spend two months working intensely with his frenemy Paul Gauguin. People don’t know that the tension hit a fever pitch, and, in a fit of depression-induced dementia, Van Gogh threatened Gauguin with a knife before turning it on himself, mutilating his ear lobe, wrapping it up in paper, and gifting it to a prostitute at a nearby brothel. They don’t know that this was the first psychotic break that led to his hospitalization, and then subsequent commitment into a mental institution in Saint-Remy, where, between fits of madness, he painted what people do know, Starry Night. People also don’t know that the night he cut off a piece of his ear he was only a year-and-a-half away from taking his own life, at the age of 37. And people don’t know that the person who tended to him in the aftermath of that night, who took him to the hospital, and stayed by his bedside, was his dear friend, surrogate brother, and protector, the postman Joseph Roulin.

[05:59]

But, looking at this painting, we feel like we do know this, at least the last part. We look at this portrait of a serious yet approachable man, in his formal uniform and relaxed pose, his calm blue eyes locking into ours, and we feel like we know him. He’s unsmiling, but open; dignified, but warm, paternal, and accessible. And the fact of the matter is, it’s because Van Gogh cared so deeply about this man, and because he had so fine-tuned his painting style to be such a direct reflection of his highly emotional and empathic soul, that we feel a strong sense of connection. We are seeing Joseph Roulin through Van Gogh’s eyes. “I should like to put my appreciation, the love I have for him, into the picture,” Van Gogh wrote in a letter to his brother, Theo. “So I will paint him as he is, as faithfully as I can—to begin with. But that is not the end of the picture.”

[07:15]

That’s the thing about Van Gogh. Even his portraits of other people are self-portraits. And just like that, Post-Impressionism once again rears its subjective head. A quick refresher: Post-Impressionism was that idiosyncratic time between the end of the Impressionist exhibitions in 1886 and Paul Cezanne’s death in 1906. The name came later, thanks to critics cataloguing the past – no one at the time would have called himself a Post-Impressionist. This period saw many artists that we’ve heard of – Van Gogh, Cezanne, Gauguin, Seurat, Toulouse-Lautrec – experimenting with the Impressionist palette in the pursuit of something loftier than light. Impressionism let them paint modern life in vibrant colors and quick, visible brushstrokes, but now what were they going to say about it? Though in many different styles, they almost all chose to say something about subjectivity, about how the eye perceives its own reality because we’re all coming at the world from our own unique viewpoints. I know, if you’re a regular listener, this is an old song by now. But Van Gogh was particularly interested in color, and how, like the German Expressionists would very soon explore, it can affect your emotional sensibility, your mood. Van Gogh was a kind of proto-Expressionist, experimenting with high-keyed colors and thick, juicy, impulsive brushstrokes that capture reality itself as it bends to your perceptions.

[09:03]

Van Gogh, “The Night Café” (1888)

What do I mean by this? Well, remember when we looked at Cezanne’s apples, how he was painting the still life as he perceived it. To us it looks wonky and perspectivally illogical, but according to his continually changing perspective, it was pretty darn accurate. There, he was guided by intellectual reasoning, seeing if he could objectively paint a subjective viewpoint. Van Gogh, meanwhile, is guided by his emotions. And we all know how those can color our perspectives, for better and for worse. Take his painting “The Night Café” from 1888, the same year as the Postman. It’s a jarring, downward angled, mustard-colored interior of a middle-of-the-night bar, with a high-contrast pool table that looks like it’s about to slide right into you. The tables along the walls are half-lit by the glowing gas lights above, and occupied with slumped drunks and prostitutes, or empty chairs and abandoned, half-empty glasses. It’s a sinister scene, painted with violent, exaggerated brushwork and the “clash and contrast of the most alien reds and greens” in Van Gogh’s own words, which creates “an atmosphere like the devil’s furnace, of pale Sulphur.” This is a Van Gogh suffering from insomnia, teetering on the edge of sanity, and attempting to capture, as he put it, “the terrible passions of humanity by means of red and green.” It seems miserable to have experienced. Honestly, it’s pretty miserable to describe. And believe me, it’s not much more fun to look at.

[11:01]

And certainly not when compared to the Postman, which serves as a clean breath of fresh air, and was painted during a period where Van Gogh was clear-minded and confident. Sitting at the kitchen table with a close friend whom he admired and trusted. Van Gogh paints the stillness and comfort of that trust in gentle brushstrokes and calming blues: the background, his uniform, his eyes. And this comfort is so available to us, because, as we see with Night Café as well, the exquisite intimacy of Van Gogh’s paintings stem from those colors that are one and the same with his mood, his reality bent to his perceptions, and consequently bending ours. Because of the visceral effect that color has on us, as viewers, we suffer and exalt with him. Van Gogh was painting the palette of his feelings in real time, and because they’re rendered with such expressive strokes, and such dynamic color, he brings us along for the ride.

But it’s important not to lose sight of the fact that he’s always in the driver’s seat. It’s so easy to get swept away with his interpretation of the world, and the effect that it has on us, that we forget that it is his interpretation. It’s not for nothing that he was so admiring of Gauguin, who made a career out of painting the version of Tahiti that he wanted to live in, not the one he actually inhabited. It was Gauguin who inspired Van Gogh to paint a portrait not just from life, but from memory, as he often did. Gauguin was all about painting through intuition, painting as you feel, even if it distorts reality, and Van Gogh took this permission and ran with it. Still though, it’s one thing to compromise fidelity if you’re painting an interior scene, or a landscape, or a bedroom. It’s another to paint an actual person’s portrait, and even identify him in the title, when, really, it’s a painting about you.

[13:18]

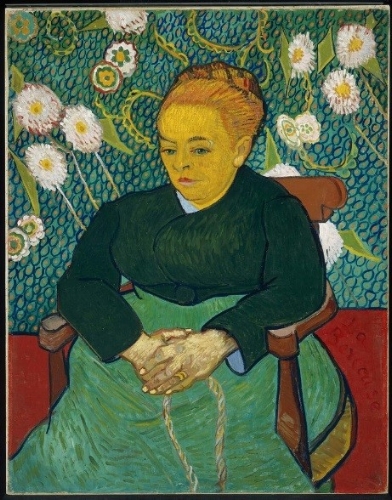

Van Gogh, "Lullaby: Madame Augustine Roulin Rocking a Cradle" (1889)

Van Gogh, "Portrait of Postman Joseph Roulin" (April 1888)

Of course, this isn’t the first time in our explorations of portraiture implicate the artist. Modern portraits in particular have a tendency to recognize the presence of the artist, and by association the viewer, and blurring the line between the two by calling our attention to the way that the artist, like the viewer, is infiltrating the space that the sitter occupies. We, like John Singer Sargent was, are ignored by the oldest Boit daughter, and we, like Degas couldn’t, aren’t able make his cousins sit still long enough to paint them. And the portrait’s sitters are more authentic for it—of course, given her druthers, a moody adolescent is going to turn away from you trying to paint her. But this is the first time we’re seeing an artist’s subjective filter color the actual sitter. Maybe Gauguin’s fantasies were coloring his whole Tahitian world, but he wasn’t zeroing in on one person in particular. But here, Van Gogh is. He is painting his friend. And his friend now becomes our friend. So who is he?

[14:43]

Joseph Roulin was born in 1841 in a southern French town in Prove-nce. At the time of these paintings, he was 47 years old, married with three children, and working as a postman in the train station at Arles. He wasn’t a mail carrier, it should be said, but held a higher rank as a mail sorter, as evidenced by his uniform, which he apparently wore day and night. Clearly, being a postman was an important part of his identity and a source of pride. Van Gogh was a true admirer of the working class, and you can hear his reverence in his description of Roulin: “a postman in a blue uniform, trimmed with gold, a big bearded face, very like Socrates.” And it’s important, this attention that Van Gogh calls to Roulin’s uniform, and to his beard. The uniform is painted with utmost significance. People often think that he’s a sailor until they read his cap, and even the wall text describes how Van Gogh gives Roulin “the authority of an admiral.” The elegant loops of the gold stitching around the cuffs are as close as Van Gogh ever gets to tight graphic design, and the double-breasted buttons pop out against the dark blue like coins. It doesn't feel like he’s wearing the uniform, it feels like he’s it, inseparable from it. But where the uniform is well-pointed and official, then there’s also that beard. It’s the only stylized element in the painting, the only part that feels classically Van Goghy, with the swirly turbulent brushstrokes that we associate with Starry Night. This beard is in a league of its own, a visual attention grabber, and especially significant, given Van Gogh’s comparisons of Roulin to Socrates, and to the author Fodor Dostoyevsky, as a stand-in for the kind of loyalty, compassionate protection, and scrappy blue collar wisdom that Van Gogh found in Roulin, who himself was a socialist, a man of the people, with fiery populist politics and a nose reddened from drinking.

[17:04]

Van Gogh and Roulin lived on the same street and probably met as neighbors, which soon became drinking buddies, and then close friends as Roulin invited the loner Van Gogh to meet his family, where Van Gogh found the free models of his dreams. It's lovely to see how Van Gogh realizes his painterly fascination with modern portraiture alongside his affection for this adoptive family. There are multiple portraits of Joseph, his wife Augustine, many that share an identical background, and are often displayed together like 17th c. Dutch marriage portraits. There are several canvases of their eleven and sixteen year old sons, Camille and Armond, against strikingly colorful backgrounds, looking alternately bored and distracted; like the Boit daughters, they’re just acting their ages. Meanwhile, Augustine had given birth to their daughter Marcelle over the course of the portrait sittings, and some of the quietest paintings from this period are of mother and daughter, rendered in blue and yellow. These portraits are tender, intimate, and exceptionally easy to look at.

Van Gogh, "Portrait of Madame Augustine Roulin and Baby Marcelle" (1888)

Because that’s what happens when you put yellow and blue side-by-side. Optically, it’s universally easy to look at. And the fact that we all feel this way, manipulated by color, sometimes aggressively, and sometimes gently, is another important component of what Van Gogh wanted the modern portrait to be. Because anything that speaks to the masses like this isn’t just artistic, it’s political, too. A portrait of a person could be a portrait of society, he thought; a postman could be both his dear friend and a noble hero of the working class. A mother and baby could be rendered in their cozy privacy and representative of the abstract maternal affection that we all hunger for. And this is the modern portrait to Van Gogh: a canvas upon which to process his own experiences, prioritizing the intensity of feeling over the fidelity to the subject, and then using this creative, colorful license, to speak to something bigger. Something universal.

[19:36]

Van Gogh, "Armand Roulin" (c. 1888); "Camille" (c. 1888); "Portrait of Marcelle Roulin" (1888)

And maybe this explains the ear thing. In a way, it’s like we all want a piece of him. This oddly specific little body part inspires a kind of universal compassion and familiarity, and maybe even a desire to protect him from himself. And we might want to think about where this desire comes from. Maybe that ear isn’t a sign that we should pity him, but rather, that he’s actually achieving what he set out to do, and our pity is a little misplaced. There’s a method to his madness, and the fact of the matter is, we wouldn’t care if he hadn’t been enormously successful in his approach. So yes, Van Gogh suffered enormously in his all-too-brief life. We know this. We’ve got a piece of his ear to prove it. But let’s not confuse this with, as he would say, the end of the picture.

[20:44]

End credits.

[22:08]

Next time on The Lonely Palette…

TOUR GUIDE: What you see is an ordinary porcelain urinal, it’s rotated ninety degrees and on the rim, there’s an inscription “R. Mutt 1917.”

VOICE 1: I see… I see a toilet. That’s what I see.

VOICE 2: Is it, is it art? [laughs]

VOICE 3: Looks like a urinal. [laughs] I guess it’s art in its own form, right?

[22:52]