Episode 10: Piet Mondrian, "Composition with Red, Yellow, and Blue" (1927)

[01:02]

VOICE 1: Um… well… it’s mostly white, and there’s squares.

VOICE 2: I’m looking at a geometrical abstract painting, which is white but with pieces of color.

VOICE 3: The painting has one, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight, nine… squares and rectangles.

VOICE 2: And some of the squares have color and some don’t.

VOICE 4: Small red, small yellow and a larger blue square.

VOICE 2: The white makes me look, even though most of it is white with black lines, it’s making look for the red, the yellow, and the blue.

VOICE 5: Well, um, it’s, it’s very flat, there’s no, um, gradience of colors.

VOICE 6: It actually kind of reminds me of a computer monitor, a little bit.

VOICE 7: I, I realize when I’m describing it, I think, “Oh gosh, does it evoke any picture?” And I think it… [laughs] It doesn’t. [laughs]

[02:08]

VOICE 8: It is in a sense, a feeling of tidiness. There’s some order, but there are unique, interesting places that are different. But they’re fit together.

VOICE 2: So it’s like as I look around, I’m looking for the symmetry, but I’m noticing the things that are the exception… to the rule.

VOICE 4: Some of the squares have a different shade of white.

VOICE 9: This big white square, like really stands out and kind of seems to, almost float in front of those other squares.

VOICE 10: And I like the whites, the different whites, and they seem to quietly vibrate and hum a little bit.

VOICE 9: Yeah, and it is peaceful.

VOICE 10: It’s very calm painting, and it’s very soothing, in a way.

[03:02]

VOICE 11: The painting has no border. Um, and to me, just because some of the squares are incomplete, it’s like a camera lens is on a very small area of something that’s a lot larger. As if, there’s an entire field with tiles all over it, um, that I would feel so calm looking at. And that’s good enough for me. [laughs]

[03:23]

Intro credits.

[04:02]

My artist mom has a favorite saying, inherited from her favorite art teacher, which she used to trot out whenever we were having trouble with this or that artwork. To really understand this painting, she’d say, you need a chair. Just sit with it for a while. Lean in and squint and stare and eventually it will reveal itself.

Of course, that doesn’t work with every painting. To understand the works of the Renaissance, for example, it sure helps to have a bible. To understand Degas, it might help to have a few Daumier caricatures or Japanese woodblock prints at the ready. But as we get deeper into the 20th century, after, as we’ve discussed, Papa Cezanne has sanctioned artists to treat the canvas as a tool for experimentation, artists became more and more comfortable toying around with using art to elicit a feeling, or solve a visual problem, or play with an artistic concept. If you’re a particularly innovative artist, you can do that without a reference to a known story or even a recognizable object. So those objects and stories, little by little, started getting edged out. A canvas could be distilled down the essentials and still do its job. Because its job has changed.

[05:30]

Unfortunately, what makes artists more comfortable has a tendency to make us viewers less so. We expect our art to be at least somewhat legible, to grab us by the hand and tell us why we should care. And without a narrative or an object, there’s no handgrab. And without the handgrab, there’s no hope of a headpat. I mean, if we don’t really know what we’re supposed to be getting out of an artwork, then there’s no reward for understanding. So as a viewer, confronted with, for example, this Mondrian, you’re not really left with much. Except a chair.

Ladies and gentlemen, we have arrived at pure abstraction. What is abstraction? Well, to be honest, it’s easier to ask what abstraction isn’t, because it has a tendency to be defined not by what it is, but by what it lacks. And what it lacks is pretty much everything art is supposed to have, at least up until the nineteen-teens. So let’s empty this suitcase item by item. Abstraction, in its purest state, has no overt narrative. It has no represented object. It has no emotional content. It has no facture, or the evidence of an artist’s hand. It has no hierarchy, or a fore-middle-or background, telling us where to enter, and what to look at first. Heck, most times, it doesn’t even have a title. And it’s fascinating to think about what paintings that do have all these things are, really, and what they ask of the implied relationship between the viewer and the artwork. They’re the storytellers and we, in turn, look and read and process and understand. Even when a painting goes off the conventional rails, like Picasso’s Portrait of a Woman did, it still has something to tell us. It’s a woman. It’s in the title. But abstraction changes the rules. How are we supposed to interact with this painting where all the recognizable elements have been stripped away? A painting that can’t even be read, let alone interpreted? Well, it can be experienced.

[08:06]

So take a seat. Stare. It is hard to resist the urge to read it, because that’s how we’ve been trained, so give it a try. Well, in a sea of squares, we have a large white square that’s slightly off-center, surrounded by smaller squares, and three, in particular, of varying sizes, that are colored in red, yellow, and blue. These are the primary colors, as you’ll remember from kindergarten, they, along with black and white, are the foundation for every other color on the color wheel. So we’ve got primary colors and elementary shapes and…that’s it. It’s pretty basic. But what’s interesting, as you start to give yourself over to this object, is that the longer you look at this painting, the more it does. That large white square is actually a different color white than the white squares around it, and suddenly its white creaminess is contrasting with the slightly cooler grayish white it’s surrounded by. And though it’s off-center, it’s not unbalanced. It’s actually completely, beautifully balanced. Its verticals and horizontals are held in a kind of active, pulsing harmony, or, as Mondrian called it, a “dynamic equilibrium”, that radiates the kind of calm tension that can only come from the balance of opposites, those verticals and horizontals. Everything is floating perfectly in its right place.

[09:48]

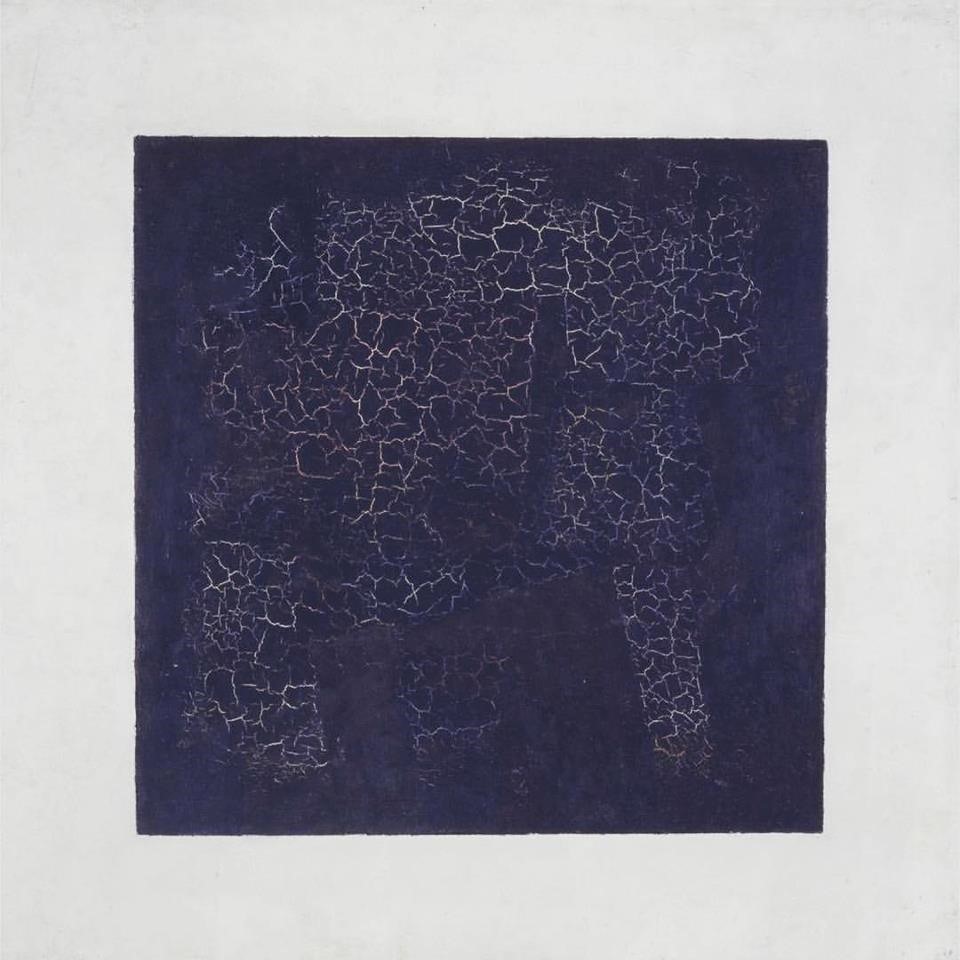

Kazamir Malevich, "Black Square" (1915)

This clarity of technique, Mondrian once wrote, accompanies the clarity of ideas. But what are the ideas? Are there any? This is why people tend to be put off by abstraction at best and blindly terrified of it at worst. Because when there’s nothing to hang ones hat on, narratively speaking, it can almost feel like the artist has absolved himself of responsibility – look, he didn't even have the courtesy to provide a title – and then it must on the viewer to create something out of, effectively, nothing. We the viewers are on the hook to make all the meaning, because, as with most blank slates, the meaning you get out of it is the meaning you put into it. And if you find this work to be confusing, or inaccessible, or utterly superfluous, then all you’ll get in return is a brick wall. So, people conclude, let those pretentious academic snobs, who somehow manage to create a doorway in, have it. Me, I like a title.

[11:05]

Ironically, this is a case of bad PR. The roots of abstraction lie in revolutionary Russia at the beginning of the 20th century, and was created as a means of democratizing art. In other words, creating art that everyone can understand, believe it or not. Kasamir Malevich, the founder of the abstract Russian movement Suprematism, describes his “desperate attempt to free art from the burden of the object” by exclusively painting squares and removing art from the grips of narrative and social context. There is a visual utopia out there, he argued, one that is unyoked from the emotion and drama and headache of art that reflects its context. After all, who made the rules of that context? The academy, the elites, the ruling class, the people telling you what art should be, but then keeping it for themselves in their fancypants museums. And this universal utopia would only be achieved when art was divorced from this context, from subjectivity, from narrative, and distilled down to its basic forms: circles and squares and primary colors. Everyone can read those, he argued. Illiterate farmers, who constituted the majority of the Russian population, and were primed to rise up in revolution, can surely recognize a square.

[12:39]

Jean-François Millet, "The Gleaners" (1857)

As you can imagine, this backfired even in its own day. Russian peasants were far more inclined towards realistic, idealized paintings of peasants than of this puzzling floating rectangle that was ostensibly painted for them. But Piet Mondrian, a Dutch painter of the same generation, inspired by Picasso’s cubes in the early 1910s, but isolated from the larger art world due to the Netherland’s neutrality in WWI, took this democratic idea of abstraction in a new, different direction. Stuck in Amsterdam during the war, he co-founded De Stijl, or “The Style”, a Dutch journal that gave the subsequent movement its name. De Stijl advocated these ideas of abstraction and universality, following in the footsteps of Russian abstraction by paring down painting, architecture, furniture, and design to their essentials – lines and shapes and primary colors. But rather than rallying peasants, and appealing to the universality of our innate ability to recognize shapes, De Stijl, and Mondrian in particular, took this idea of universality to a higher calling, a new kind of unifying utopia. Abstraction went from a democratic rallying cry to a spiritual purification of the mind and soul. That sense of calm and heightened dynamic rationalism that we get from sitting and staring at these pulsing abstract paintings is actually, they argued, a deeply spiritual experience, a transcendence to a higher plane that you’d never be able to achieve on your own. Not on this planet, at least. And not without this art. Mondrian wanted his canvases to act as a green room for your eyes, a KonMari for your psyche, an offer to transcend the unruly, traumatic mess of the empirical, experienced world.

[14:49]

Gerrit Rietveld, "Red and Blue Chair" (1917)

Because really, that’s what’s at the heart of all this. Mondrian isn’t the first artist we’ve looked at who lived through World War I, but unlike the German Expressionists, who dug into the muck up to their elbows, his response to witnessing this trauma was to transform disorder into order. Nature, he concluded, be it greenery or humanity, was too wild, too unpredictable, too unconstrained for his tastes. It’s been said, perhaps apocryphally—but I hope not—that he used to ask to face away from windows in restaurants, that looking out at trees took away his appetite. It was the “irregularities” of nature that accounted, in his mind, for everything that was wrong with humanity, and this abstract art, these universal forms, arranged in this deeply balanced asymmetry, would transcend these divisions and become our new common language. While modern artists across Europe were addressing one or another particular piece of the aesthetic pie, Mondrian was creating a new pie altogether, a utopian pie that had no room for subjectivity, or human nature, or mess, and that there’s no coming back from. Now that we have arrived at this point, he believed, his is the last art that needs to be. And he is the last artist.

[16:29]

You know, I said at the top that abstract art lacked emotion, and it would seem that Mondrian’s spiritual roadmap would confirm that. As we’ve discussed, Abstraction is objectivity and rationalism and defined by what it lacks. If you asked it what emotion was, it would look at you quizzically, like when I call my cat by its name. It’s just not in its vocabulary. Yet in Mondrian’s hands, abstraction isn’t unemotional because it never had any to begin with, it is, instead, the active rejection of emotion. He is making the choice to value order over disorder. There’s comfort and predictability in a grid. He embraces the rigid lines because curves, he wrote, with no small trace of haughtiness, “are so emotional.”

[17:31]

You can choose, or not, to buy what Mondrian is selling, to join him in this Utopian transcendence, but it seems that by his making this choice, order over disorder, he actually takes his rightful place among us again. Because, as a viewer, what’s powerful about giving yourself the permission and space to stare at this painting for long periods of time, is that you start to notice those tiny irregularities anyway. This image wasn’t generated by a computer, it was in fact painted by a human hand. Focus closely on the black lines and you start to see just a tiny wobble, an almost imperceptible thickening of the band where he couldn’t hold the perfect straight line as he drew the brush down the canvas. Spiritual and self-important as Mondrian described his art to be, at its core, it was a response to trauma, simultaneously as valid and as limited as any other, and moreover a deeply human response to his own wildness, his own unpredictability. So he chose a grid instead. And maybe that, too, is something we can all relate to.

[19:00]

End credits.

[20:39]

Next time on The Lonely Palette…

VOICE 1: Uh, picture yourself in a room, and it probably smells like an old book.

VOICE 2: I have a little bit of that Downtown Abbey going on.

VOICE 3: You’ve got the little girl in the front, the shy girl a little to the left, the older sister… very bored, wishing she was anywhere else.

VOICE 4: The four girls are looking directly at us, actually they’re kind of saying “why are you looking at me? What’s so amazing about this?” And there’s a lovely interaction between them and me, they are sort of inviting me into their living room. Uh, I happen to love this painting.

VOICE 5: The figure towards the left, uh, I can hear her saying “Well so, this is our living room, you can come look around, see the things that my dad got.”

[21:33]